Limited treatment access drives poor PNH outcomes in South India

Researchers say study highlights need for wider availability of C5 inhibitors

Written by |

Improved access to standard-of-care treatments could significantly improve outcomes for people with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) living in South India, a study found.

The researchers said poor outcomes, including frequent complications, repeated hospitalizations, and increased mortality, were largely driven by greater reliance on supportive care in the region.

“Supportive care … is associated with poor outcomes, highlighting the need for improved access to standard of care treatments,” the scientists wrote.

The study, “A Retrospective Analysis of Characteristics and Outcomes of Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria Patients, not Having Access to Standard of Care,” was published in the Indian Journal of Hematology and Blood Transfusion.

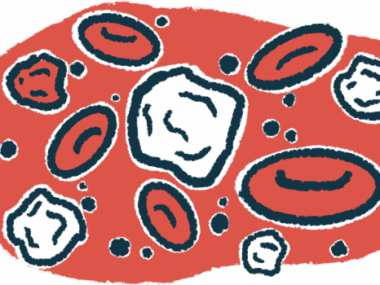

PNH is marked by the destruction of blood cells, particularly red blood cells, due to abnormal activation of the complement system — a part of the immune system that normally helps fight infections. PNH symptoms include dark-colored urine, low blood cell counts, blood clotting problems, and bone marrow dysfunction.

Treatments transforming care, but access for some remains limited

Over the past two decades, PNH treatments that block the complement system have transformed standard care. Drugs such as Soliris (eculizumab) and Ultomiris (ravulizumab), known as C5 inhibitors, bind to the complement protein C5 and ultimately block activation of the complement system.

These therapies reduce red blood cell destruction, lower the risk of blood clots (thrombosis), and significantly improve quality of life for people living with PNH.

However, access to standard-of-care treatments remains limited in many parts of the world.

“Although the efficacy of C5 inhibitors in PNH management is irrefutable, their use is limited by their cost, and they may not be accessible in many resource limited settings,” the researchers wrote. “Only supportive care is available for PNH patients in many countries like India.”

The researchers reviewed the clinical features and outcomes of 45 people diagnosed with PNH . The study, conducted between January 2018 and July 2024, followed the patients at a tertiary care center without access to C5 inhibitors.

Patients’ median age at symptom onset was 35. Most (93%) were initially referred for low blood count (cytopenia). Pancytopenia (a reduction in red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets) was observed in 59% of cases.

Seven patients (15.5%) had thrombosis, more often affecting veins in the abdomen or brain. Five patients (11.1%) had hemoglobinuria, a condition in which hemoglobin — the oxygen-carrying molecule in red blood cells — in the urine makes the urine appear dark. Nine patients (20%) had more than one symptom.

Diagnosis was frequently delayed. A mean delay of 1.88 years was observed between symptom onset and PNH confirmation, with one patient remaining misdiagnosed for nearly 18 years. The researchers noted that these delays might be largely due to overlapping symptoms with more common disorders and limited access to specialized diagnostic testing.

Hormone-based therapy with danazol was given to 64.4% of patients, while 42% received immunosuppressing drugs known as calcineurin inhibitors.

Medications aimed at stimulating platelet production were used in 33.3% of patients, and 28.8% received corticosteroids. Five patients (11%) were treated with anti-thymocyte globulin, a therapy commonly used for bone marrow failure.

The median follow-up time was 2.49 years, during which patients had an average of more than two hospital admissions, ranging from none to 16.

Signs of ongoing red blood cell destruction were more common than clotting-related complications during follow-up. Thrombosis occurred in 15.5% of patients.

Thirteen of the 45 patients (28.8%) died during follow-up, while three were lost to follow-up. The most common causes of death were severe infections and internal bleeding.

Overall, 57.6% of patients were still alive five years after diagnosis, which the researchers said highlights the serious risks faced by people with PNH when the disease is managed without access to standard complement-inhibiting therapies.

“Lack of access to standard of care i.e. complement inhibitors, may be the reason for increased mortality and increased incidence of other complications like thrombosis and hospital admissions seen in our [group],” the researchers concluded. “There is a glaring need for making the standard of care available to patients with PNH in countries where resources are limited.”