Direct oral anticoagulants prevent recurring blood clotting in PNH

Study finds medications effective when given after standard treatments

Written by |

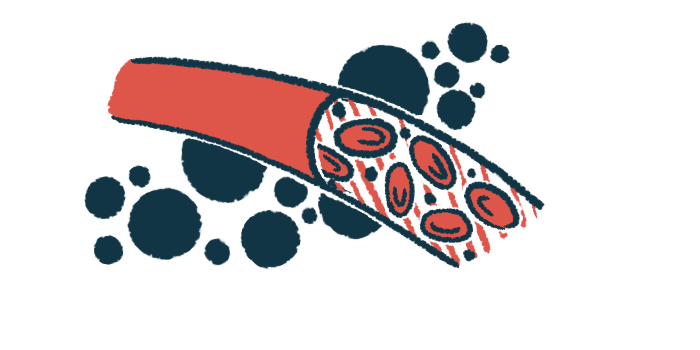

Direct oral anticoagulants, or DOACs, are safe and effective for preventing recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE), or blood clots forming in a vein, in people with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), a study reports.

These medications, given after standard vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) during the acute phase of VTE, helped prevent further VTE events.

“Our retrospective monocentric analysis shows that DOACs could be an effective and safe choice in this setting,” researchers team wrote.

The study, “Direct oral anticoagulants as secondary prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: an Italian monocentric experience,” was published in the Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis.

Study seeks data on use of direct oral anticoagulants in PNH

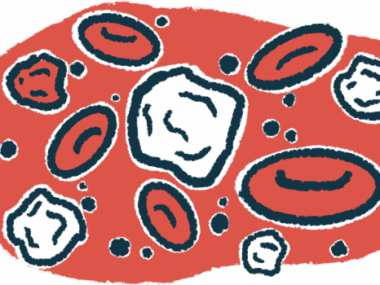

In PNH, immune destruction of blood cells can result in sudden attacks of symptoms like fatigue and shortness of breath. Genetic mutations in hematopoietic stem cells, the precursors to all types of blood cells, typically cause these mistaken immune attacks.

Up to 44% of individuals with PNH experience at least one VTE event. Such incidents impede the flow of oxygen-poor blood through the veins toward the heart. Clotting problems like VTE are the leading cause of death in PNH.

The complement system, a cascade of proteins that is part of the immune system, is involved in the abnormal immune attacks against blood cells. Approved PNH treatments, which have emerged in recent decades, block complement system signaling to bring the immune response into check, and may also reduce VTE risk.

VTE in PNH has been traditionally managed with VKAs and LMWH, but DOACs have become the mainstay treatment in most settings. This is due to DOACs’ “predictable pharmacokinetics [movements into, through, and out of the body], fixed dosing, and no need for laboratory monitoring,” the researchers wrote.

While DOACs are a standard VTE treatment in many settings, there is little data about their use in PNH. In particular, it is unclear how DOACs could prevent recurrence of VTE after it has already occurred once in people with PNH.

To learn more, a team of researchers in Italy retrospectively analyzed data from 30 PNH patients taking DOACs as secondary preventive treatment for VTE after receiving VKAs and LMWH during the acute phase of VTE.

They had received a PNH diagnosis between 1990 and 2025. Their median age at disease onset was 32 years, and 16 were female.

Anti-complement therapies were begun a median of 2.6 years after diagnosis, with eculizumab (sold as Soliris, with biosimilars available) being the first used. After that, 66.7% of patients were switched to new anti-complement treatments.

No adverse events directly related to DOAC treatment

Data showed that “the introduction of anti-complement treatment reduced the incidence of venous thromboembolism,” the team wrote.

Specifically, VTEs were reported in seven people (23.3% of all participants) before eculizumab became available, compared with no patient after the therapy’s availability.

One participant had recurring VTEs in the lower limbs, a common location for this type of clots. The other six had an atypical presentation, with clotting in the kidneys, abdominal veins, or a vein in the skull.

After initial treatment, all seven individuals began on VKAs and LMWH, then later switched to DOACs, which were given for a median of 8.4 years.

The introduction of anti-complement treatment reduced the incidence of venous thromboembolism.

All but one of these seven patients were taking eculizumab when they began DOAC therapy. Most have since switched to alternative complement inhibitors.

After a median of 17.1 months (nearly 1.5 years) of follow-up, “no VTE recurrence was observed,” the researchers wrote.

Although results were mostly similar on the different types of medication, “two young women reported a reduction in menstrual bleeding intensity after the shift from [VKA] to DOACs,” the team wrote.

There were no adverse events directly related to DOAC treatment, and all participants were still alive at the most recent follow-up. However, two individuals experienced clinically relevant but non-major bleeding episodes. During bleeding, they temporarily discontinued DOACs, then began again seven days later.

While these results indicate DOACs are safe and effective for preventing recurrences of VTE in PNH, “further data is needed to create guidelines for a standardized anticoagulation approach and its length in this setting,” the researchers wrote.

Specifically, the team suggested future investigations focus on how and when to safely discontinue DOAC use.